How to Read Sheet Music: Expert Guide

How to Read Sheet Music: Expert Guide

Sheet music might look like an intimidating maze of dots, lines, and squiggles at first glance, but here’s the truth: learning to read it is far more achievable than you think. Whether you’re picking up an instrument for the first time or finally deciding to decipher those mysterious symbols you’ve been avoiding, this guide will walk you through everything you need to know. Think of sheet music as a universal language—once you understand the basics, you can play virtually any composition ever written.

The beauty of reading sheet music is that it opens up an entirely new world of musical possibilities. Instead of relying solely on ear training or memorization, you gain access to centuries of classical compositions, modern arrangements, and everything in between. Plus, understanding sheet music actually accelerates your learning on any instrument, whether that’s piano, violin, clarinet, or even harmonica.

This comprehensive guide breaks down sheet music from the ground up, covering everything from the staff and clefs to rhythms, dynamics, and interpretation. By the end, you’ll feel confident tackling sheet music with genuine understanding rather than blind guessing.

The Staff: Your Musical Foundation

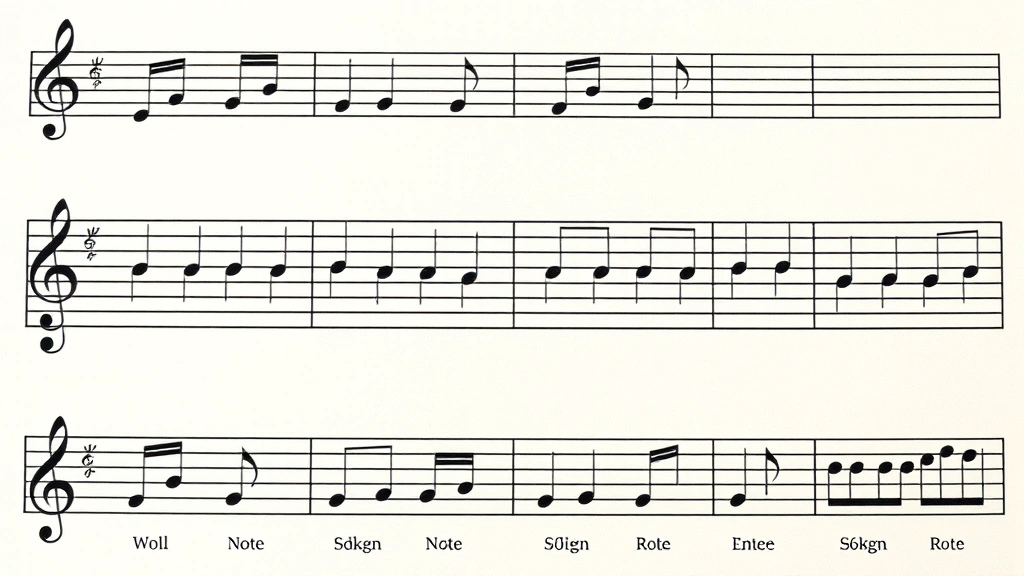

Every piece of sheet music starts with the staff, which is essentially the canvas upon which all musical information is painted. The staff consists of five horizontal lines and four spaces between them. These lines and spaces represent different pitches, and their meaning changes depending on which clef you’re using.

Think of the staff like a ladder where each rung represents a specific note. The position of a note on the staff tells you which pitch to play. Lines are numbered from bottom to top (1 through 5), and spaces are numbered the same way. This simple system has been used for hundreds of years because it’s incredibly effective at communicating pitch information visually.

At the beginning of every staff, you’ll notice a symbol that looks somewhat decorative but serves a crucial purpose. This is the clef, and it’s your first major milestone in learning sheet music. The clef essentially tells you what reference point to use for all the notes that follow. Without it, you wouldn’t know whether a note on the second line represents a high pitch or a low one.

Understanding Clefs

There are several clefs used in modern music, but three dominate: treble clef, bass clef, and alto clef. Each one shifts the reference point for where notes sit on the staff, making them useful for different instruments and ranges.

Treble Clef is by far the most common and is used for higher-pitched instruments like flute, violin, clarinet, and the right hand of piano music. It looks like a fancy G with two dots surrounding a line. That line it wraps around? That’s the G line, and it’s your anchor point. Once you know G, you can figure out every other note from there.

Bass Clef is the mirror image situation for lower-pitched instruments like cello, tuba, trombone, and the left hand of piano music. It resembles a backwards C with two dots. Those dots surround the F line, which is your reference point for bass clef. If you’re learning an instrument and wondering how your music connects to broader musical literacy, understanding both clefs is essential.

Alto Clef is less common but still important, particularly for viola players and some classical music. It looks somewhat like a C rotated 90 degrees, and the middle line represents middle C.

A practical tip: many musicians learn to memorize the lines and spaces using mnemonics. For treble clef lines, “Every Good Boy Does Fine” helps you remember E-G-B-D-F from bottom to top. Spaces spell F-A-C-E naturally. For bass clef, “Good Boys Do Fine Always” gives you G-B-D-F-A, and spaces are A-C-E-G.

Notes and Their Positions

Once you understand the staff and clef, identifying individual notes becomes straightforward. Each note has two components: its letter name (A through G) and its octave. The letter names repeat cyclically, so after G comes A again, just higher.

Here’s where many beginners trip up: the same note can appear in multiple octaves on the staff. Middle C, for instance, is the most important reference point in all of music. It sits below the treble clef staff and above the bass clef staff, making it the perfect bridge between the two. Once you locate middle C, you can navigate anywhere on either staff.

Lines and spaces follow a pattern. In treble clef, starting from the bottom: the bottom line is E, then F is in the space above it, G is on the next line, and so on. The same principle applies to bass clef, just starting from different notes. Spend time drilling this until it becomes automatic—this is the foundation everything else builds upon.

If you’re learning guitar, you might wonder how sheet music relates to what you already know. While many guitarists prefer how to read guitar tabs, understanding sheet music makes you a more complete musician and opens doors to classical and jazz repertoire. Additionally, when you how to tune a guitar, you’re already using note names—sheet music simply formalizes that knowledge.

Rhythm and Time Signatures

Knowing which notes to play is only half the battle. You also need to know when to play them and for how long. This is where rhythm comes in, and it’s communicated through a combination of note shapes and time signatures.

The time signature appears right after the clef at the beginning of a piece. It looks like a fraction (though it’s not actually a mathematical fraction). The top number tells you how many beats are in each measure, and the bottom number tells you what type of note gets one beat. The most common time signature is 4/4, which means four beats per measure, with the quarter note getting one beat.

Think of measures as containers. Each measure holds a specific amount of musical time, determined by the time signature. When you reach the end of a measure, a vertical bar line marks the boundary. This visual organization makes sheet music much easier to read and helps you stay organized while playing.

Common time signatures include:

- 4/4 (Common Time): Four quarter-note beats per measure. This is the default for most popular music, rock, and contemporary compositions.

- 3/4 (Waltz Time): Three quarter-note beats per measure. Waltzes, folk music, and many classical pieces use this signature.

- 2/4: Two quarter-note beats per measure. Often used in marches and fast-paced pieces.

- 6/8: Six eighth-note beats per measure. Common in folk music and pieces with a lilting, flowing quality.

Understanding time signatures helps you anticipate the rhythm and feel of a piece before you even start playing. A piece in 3/4 feels fundamentally different from one in 4/4, and recognizing this from the time signature alone is a valuable skill.

Duration Values and Rests

Individual notes have different durations, indicated by their visual appearance. A whole note (an empty oval) lasts an entire measure in 4/4 time. A half note (empty oval with a stem) lasts half that duration. A quarter note (filled oval with a stem) lasts one-quarter of a measure. Eighth notes (filled oval with a stem and one flag) and sixteenth notes (with two flags) are shorter still.

The relationship between note values is proportional. A whole note equals two half notes, which equal four quarter notes, which equal eight eighth notes. This mathematical relationship makes it easier to understand how notes fit together rhythmically.

Rests are equally important—they represent silence. A whole rest hangs below the second line from the top, a half rest sits above the middle line, a quarter rest looks like a stylized Z, and eighth rests have a flag like their note counterparts. Rests occupy the same duration as their note equivalents.

Duration hierarchy (in 4/4 time):

- Whole note = 4 beats

- Half note = 2 beats

- Quarter note = 1 beat

- Eighth note = 0.5 beats

- Sixteenth note = 0.25 beats

Dots add another layer of complexity but follow a simple rule: a dot adds half the note’s value to itself. A dotted quarter note equals a quarter note plus an eighth note (1.5 beats total). This notation appears frequently in music, so mastering it early pays dividends.

Key Signatures and Accidentals

The key signature appears right after the clef and before the time signature. It consists of sharps or flats that apply to every note on that line or space throughout the piece (unless otherwise modified). This tells you which key the piece is in and saves you from writing accidentals constantly.

A sharp (#) raises a note by one half-step, while a flat (b) lowers it by one half-step. A natural (♮) cancels a previous sharp or flat. If a piece has three sharps in its key signature, for example, every F, C, and G throughout the piece is played sharp unless marked otherwise.

There are twelve possible keys, and each one has a specific pattern of sharps or flats. Learning these patterns takes time, but here’s a practical shortcut: the circle of fifths is a visual tool that shows all twelve keys and their relationships. The order of sharps follows one pattern (F-C-G-D-A-E-B), and the order of flats follows another (B-E-A-D-G-C-F).

Accidentals are individual sharps, flats, or naturals that appear within the staff itself, not in the key signature. They typically apply only to the note immediately following them in that measure, though sometimes they carry through the entire measure depending on context and style.

Dynamics and Expression Marks

Sheet music is more than just notes and rhythms—it’s a complete communication system that includes instructions about how to play. Dynamics tell you how loud or soft to play, while expression marks convey the mood and character of the piece.

Common dynamic markings:

- pp (pianissimo): Very soft

- p (piano): Soft

- mp (mezzo-piano): Moderately soft

- mf (mezzo-forte): Moderately loud

- f (forte): Loud

- ff (fortissimo): Very loud

A crescendo (represented by a wedge opening to the right or the abbreviation “cresc.”) means gradually get louder. A decrescendo (wedge opening to the left or “decresc.”) means gradually get softer. These markings give your performance shape and emotional depth.

Expression marks include tempo indications like Allegro (fast), Andante (moderately slow), and Largo (very slow). Italian is the traditional language of musical expression, though modern composers sometimes use English or other languages. Tempo markings might also include metronome markings (like ♩= 120) that specify exactly how fast to play.

Other expression marks include articulation symbols. A staccato dot under a note means play it short and detached. A tenuto line means hold it slightly longer. A slur (curved line connecting notes) means play them smoothly without tonguing or re-bowing. These subtle markings transform the character of a phrase dramatically.

Putting It All Together

Now that you understand the individual components of sheet music, let’s talk about how they work together. When you approach a new piece, develop a systematic process: first, identify the clef and key signature. Next, note the time signature and tempo marking. Then, scan through the piece to spot any unusual markings or challenging passages.

Start slowly—this cannot be overstated. Your brain is processing a tremendous amount of visual information, so give it time to convert symbols into physical actions. Many beginners rush and create bad habits that are difficult to break later.

Practice reading sheet music regularly, even if it’s just ten minutes daily. Like any language, reading music improves through consistent exposure. Start with simple pieces and gradually work toward more complex arrangements.

If you’re interested in expanding your musical literacy beyond sheet music, you might explore related musical skills. While how to play spoons doesn’t require reading music, understanding sheet music can help you notate and share rhythmic patterns you discover. Similarly, if you’re curious about card games and want a mental break from music study, how to play cribbage and how to play spades offer engaging alternatives that develop strategic thinking.

Consider using Music Theory’s interactive lessons to supplement your learning with interactive exercises and immediate feedback. Websites like Classic for Kids provide excellent explanations of musical concepts, while musicca.com offers free tools for practicing note identification.

Remember that musicians at every level occasionally need to refresh their sheet music reading skills. Even accomplished musicians sometimes encounter notational quirks they haven’t seen before. The key is maintaining curiosity and approaching each new piece as an opportunity to deepen your understanding.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to learn to read sheet music?

Most people can grasp the basics in a few weeks of consistent practice. However, fluency—where you can sight-read unfamiliar pieces smoothly—typically takes several months to a year depending on your practice frequency and prior musical experience. The good news is that you don’t need to be fluent to start enjoying the benefits of reading music.

Do I need to learn sheet music if I play by ear?

While playing by ear is a valuable skill, learning sheet music dramatically expands your musical vocabulary and allows you to access compositions written specifically for your instrument. Many professional musicians use both skills together. Sheet music also helps you communicate musical ideas with other musicians and preserves compositions for future generations.

What’s the difference between sheet music and guitar tabs?

Sheet music indicates pitch and duration through position and note shape, while guitar tabs show you exactly which fret to play on which string. Guitar tabs are simpler to learn but less informative about rhythm. Many guitarists benefit from learning both—sheet music makes you a more complete musician, while tabs are practical for quick learning.

Can I learn to read sheet music as an adult?

Absolutely. While children’s brains may absorb information slightly faster, adults often make excellent progress because they bring discipline, focus, and clear motivation to their practice. Many successful musicians picked up reading music well into adulthood. Your age is far less important than your consistency and willingness to practice.

What if I struggle with memorizing note positions?

Struggling initially is completely normal—you’re learning a new visual language. Use mnemonics like “Every Good Boy Does Fine” for treble clef lines. Write out the notes on staff paper repeatedly. Use flashcards or apps like Music Theory that gamify the learning process. Most importantly, practice daily even if just for short sessions.

Are there different types of sheet music notation?

Yes. Standard notation (what we’ve covered) is universal for most instruments. However, some instruments and genres use specialized notation. For instance, guitarists often use tablature, drummers use percussion notation, and contemporary composers sometimes use graphic notation. Learning standard notation first gives you the foundation to understand these variations.

How do I read music faster?

Speed comes naturally with practice and familiarity. Focus on accuracy first, then gradually increase your pace. Use a metronome to push yourself slightly beyond your comfort zone. Practice sight-reading different pieces rather than perfecting the same piece repeatedly. Your brain will develop pattern recognition that accelerates reading over time.