How to Find Limiting Reactant: Easy Guide

How to Find Limiting Reactant: Easy Guide

Chemistry can feel intimidating, especially when you’re staring down a chemical equation wondering which ingredient will run out first. But here’s the thing—finding the limiting reactant isn’t some mystical dark art reserved for lab coats and beakers. It’s actually a straightforward process that follows logical steps, and once you understand the concept, you’ll wonder why it ever seemed confusing.

Think of it like baking cookies. If a recipe calls for two cups of flour and one cup of butter, but you only have half a cup of butter, that butter is your limiting ingredient. You can’t make the full batch no matter how much flour you have. Chemistry works the same way. The limiting reactant is the ingredient that gets used up first, determining how much product you can actually make.

Whether you’re tackling a high school chemistry assignment, preparing for an exam, or just curious about how reactions work, this guide breaks down the concept into digestible pieces. We’ll walk through practical examples, show you the math, and give you strategies to solve these problems confidently.

What Is a Limiting Reactant?

A limiting reactant is the substance in a chemical reaction that determines how much product gets formed. It’s the ingredient that runs out first, stopping the reaction in its tracks. Once it’s gone, the reaction can’t continue, no matter how much excess reactant remains.

Every chemical reaction involves reactants combining in specific ratios called stoichiometric ratios. These ratios are determined by the coefficients in the balanced chemical equation. When you have exactly the right amounts of each reactant according to these ratios, you’re in an ideal scenario. But in real life, that rarely happens.

The excess reactants are the substances left over after the limiting reactant is completely consumed. These materials don’t participate further in the reaction because there’s nothing left to react with them. Understanding which reactant is limiting helps you predict how much product will form and identify which materials you’ll have leftover.

Why Does It Matter?

Understanding limiting reactants has practical implications beyond passing chemistry tests. In industrial settings, manufacturers use this concept to optimize production and minimize waste. They want to order the right amounts of raw materials so nothing gets wasted while still producing maximum output.

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, getting the limiting reactant calculation wrong could mean producing less medicine than needed or wasting expensive ingredients. In food production, it affects batch sizes and ingredient costs. Even in environmental chemistry, understanding limiting reactants helps predict pollution levels and design better cleanup strategies.

For students, mastering this concept demonstrates understanding of fundamental chemistry principles. It shows you can work with proportions, interpret equations, and think critically about chemical processes. These skills transfer to countless other chemistry topics and real-world problem-solving scenarios.

Step-by-Step Process for Finding the Limiting Reactant

Finding the limiting reactant follows a systematic approach. Once you memorize these steps, solving problems becomes almost mechanical. Let’s break it down into manageable pieces.

Step 1: Balance the Chemical Equation

Before you do anything else, ensure your chemical equation is properly balanced. The coefficients in a balanced equation represent the molar ratios between reactants and products. If the equation isn’t balanced, your entire calculation falls apart.

Balancing requires counting atoms on both sides of the equation. Make sure each element appears the same number of times on the reactant side as on the product side. This might take practice, but it’s absolutely essential. If you’re unsure about balancing equations, review that skill first before tackling limiting reactants.

Step 2: Convert Given Amounts to Moles

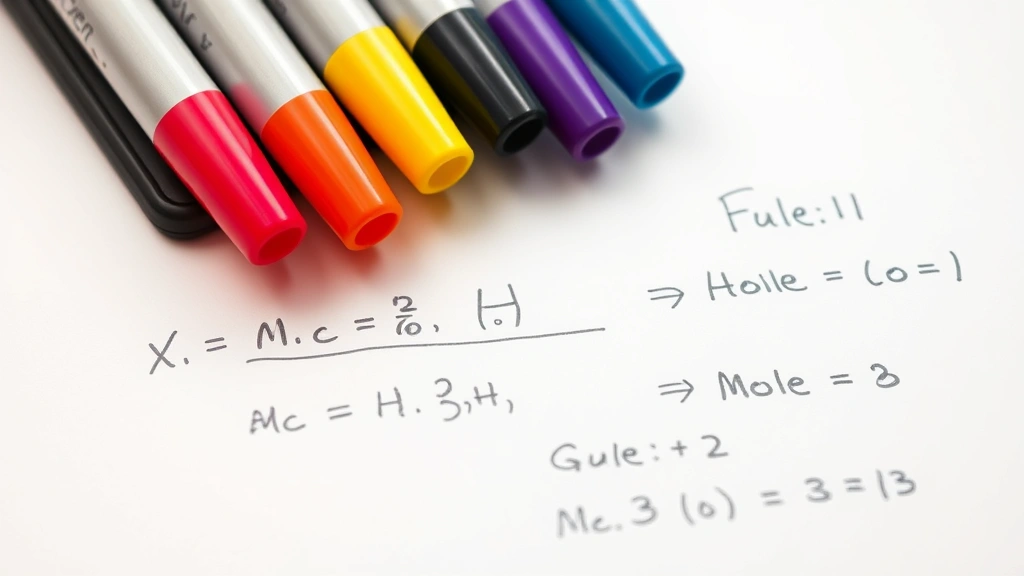

Most problems give you amounts in grams, milliliters, or other units. You need to convert everything to moles because chemical equations work with molar ratios, not mass ratios. This is where the periodic table and molecular weights become your best friends.

To convert grams to moles, use this formula: moles = grams ÷ molar mass. Find the molar mass by adding up the atomic masses of all atoms in the molecule. The periodic table provides atomic masses for each element. Keep your calculation organized and double-check your arithmetic.

Step 3: Calculate Mole Ratios

For each reactant, divide the number of moles you have by the stoichiometric coefficient from the balanced equation. This tells you how many times each reactant can participate in the reaction.

For example, if your equation shows that two moles of reactant A are needed for every three moles of reactant B, and you have four moles of A and five moles of B, you’d calculate: A can react 4÷2 = 2 times, while B can react 5÷3 = 1.67 times. The smaller number indicates which reactant runs out first.

Step 4: Identify the Limiting Reactant

The reactant with the smallest mole ratio is your limiting reactant. This substance will be completely consumed while other reactants remain. The excess reactants won’t fully participate in the reaction.

Step 5: Calculate Theoretical Yield

Once you know your limiting reactant, use it to calculate how much product forms. Multiply the moles of limiting reactant by its stoichiometric ratio to the product, then convert back to grams if needed. This theoretical yield represents the maximum amount of product possible under ideal conditions.

Worked Examples: Putting It All Together

Let’s work through some concrete examples so you see exactly how this process works in practice.

Example 1: Simple Two-Reactant Reaction

Consider this balanced equation: 2H₂ + O₂ → 2H₂O

Suppose you have 4 moles of hydrogen gas and 3 moles of oxygen gas. Which is limiting?

First, check the stoichiometric ratios from the equation. Hydrogen and oxygen combine in a 2:1 ratio. Now calculate how many times each can react:

- Hydrogen: 4 moles ÷ 2 = 2

- Oxygen: 3 moles ÷ 1 = 3

Hydrogen has the smaller ratio (2 compared to 3), so hydrogen is the limiting reactant. It will be completely consumed first. From 4 moles of H₂, you’d produce 4 moles of H₂O (since the ratio of H₂ to H₂O is 1:1). You’d have 1 mole of O₂ left over.

Example 2: Working with Grams

Let’s say you’re burning methane: CH₄ + 2O₂ → CO₂ + 2H₂O

You have 16 grams of methane and 64 grams of oxygen. What’s the limiting reactant?

First, convert to moles. Methane’s molar mass is 12 + (4×1) = 16 g/mol. Oxygen’s molar mass is 16 g/mol, but O₂ is diatomic, so O₂ = 32 g/mol.

- Methane: 16 g ÷ 16 g/mol = 1 mole

- Oxygen: 64 g ÷ 32 g/mol = 2 moles

Now check the stoichiometric ratios from the balanced equation. Methane and oxygen combine in a 1:2 ratio. Calculate:

- Methane: 1 mole ÷ 1 = 1

- Oxygen: 2 moles ÷ 2 = 1

Both ratios equal 1, meaning you have exactly the right proportions. Neither reactant is limiting—they’ll both be completely consumed, and this is a perfect stoichiometric mixture. You’ll produce 1 mole of CO₂ and 2 moles of H₂O.

Example 3: Three-Reactant Scenario

Sometimes problems involve more reactants. Consider: 2A + 3B + C → products

If you have 10 moles of A, 12 moles of B, and 5 moles of C, calculate:

- A: 10 ÷ 2 = 5

- B: 12 ÷ 3 = 4

- C: 5 ÷ 1 = 5

Substance B has the smallest ratio (4), making it the limiting reactant. A and C will be in excess.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even with the best intentions, students make predictable errors when finding limiting reactants. Knowing these pitfalls helps you sidestep them.

Forgetting to Balance the Equation

This is the most critical mistake. An unbalanced equation gives you wrong stoichiometric ratios, which cascades into incorrect calculations. Always verify your equation is balanced before proceeding. If you’re uncertain, balance it again from scratch.

Confusing Coefficients with Subscripts

In the formula H₂O, the 2 is a subscript indicating the number of hydrogen atoms in one molecule. In an equation like 2H₂O, the 2 is a coefficient indicating two molecules. These serve completely different purposes. Use only coefficients for stoichiometric ratios, never subscripts.

Skipping the Mole Conversion

You cannot directly compare grams or milliliters using stoichiometric ratios. You must convert to moles first. This is non-negotiable. Molar ratios are the language chemistry uses to describe how substances combine.

Calculating the Wrong Ratio

Some students divide the stoichiometric coefficient by the moles available, doing the inverse of the correct calculation. Remember: moles available ÷ stoichiometric coefficient. The available amount goes on top.

Forgetting About Theoretical Yield

Finding the limiting reactant is only half the battle. You then need to calculate how much product forms based on that limiting reactant. Don’t stop after identifying which reactant is limiting—complete the calculation to find theoretical yield.

Tips and Tricks for Success

Beyond the basic steps, some strategies make these problems easier to tackle. These tips come from experience and can significantly speed up your problem-solving.

Organize Your Work

Write down everything: the balanced equation, molar masses, mole conversions, ratios, and calculations. This organization prevents errors and makes it easy to spot mistakes if something goes wrong. Future you (and your teacher) will appreciate the clarity.

Use Dimensional Analysis

Dimensional analysis, also called the factor-label method, ensures your unit conversions work correctly. Write out your conversions showing how units cancel, leaving you with the desired unit. This technique prevents many careless mistakes.

Double-Check Molar Masses

Incorrect molar masses throw off all subsequent calculations. Use a reliable periodic table and add up atomic masses carefully. If you’re getting unexpected answers, verify your molar masses first.

Round Appropriately

During intermediate steps, keep extra decimal places. Only round your final answer to match the significant figures in the original problem. Rounding too early in intermediate steps can accumulate errors.

Practice with Varied Problems

Work through many different problems with varying numbers of reactants, different magnitudes, and both gram-based and mole-based starting amounts. Variety builds true understanding rather than memorized patterns.

When you’re learning about calculating proportions in chemistry, it helps to understand related concepts. For instance, if you ever need to determine how to find relative frequency in data analysis, you’ll use similar proportional reasoning. Similarly, if you’re studying atomic structure, knowing how to find neutrons in an atom builds foundational chemistry knowledge. And if you’re working with statistical data, understanding how to find the range of a dataset uses comparable mathematical skills.

For additional authoritative resources, check out Khan Academy’s chemistry section for video explanations, or consult Chemistry Learner’s limiting reactant guide for interactive examples. YouTube chemistry channels offer visual demonstrations that make the concept click for many learners. For a comprehensive textbook approach, LibreTexts Chemistry provides detailed explanations and practice problems.

Frequently Asked Questions

What happens to excess reactants after the reaction?

Excess reactants remain unreacted after the limiting reactant is completely consumed. Since there’s no more limiting reactant to combine with them, they just sit there. In industrial applications, these excess materials might be recovered, recycled, or disposed of depending on their value and environmental impact.

Can there be more than one limiting reactant?

In a typical single reaction, only one limiting reactant exists. However, in sequential reactions (where products from one reaction become reactants in another), different substances might be limiting at different stages. For a single reaction event, you’ll have exactly one limiting reactant.

How do limiting reactants apply to real-world situations?

Everywhere chemistry happens in industry, limiting reactants matter. Pharmaceutical companies use this concept to calculate batch sizes and ingredient orders. Food manufacturers apply it to recipe scaling. Environmental engineers use it to predict pollution cleanup capabilities. If you’ve ever wondered why a recipe gives specific ingredient amounts, limiting reactants explain it—the recipe is designed so all ingredients are used up proportionally, minimizing waste.

Is theoretical yield always achieved in practice?

No, theoretical yield assumes perfect conditions and 100% efficiency. Real reactions rarely achieve this due to side reactions, incomplete reactions, and energy losses. Actual yield is usually less than theoretical yield. The difference between theoretical and actual yield is expressed as percent yield, which measures reaction efficiency.

Why do we use moles instead of just comparing amounts directly?

Chemical reactions occur at the molecular level where particles combine in specific whole-number ratios. Moles represent these molecular quantities in measurable amounts we can work with in the lab. A mole is simply 6.022 × 10²³ particles—a number large enough to represent visible quantities. Using moles lets us directly apply the stoichiometric ratios from balanced equations.

How do I know if I’ve identified the limiting reactant correctly?

Check your work by calculating how much of each reactant would be consumed if each one were limiting. The one that produces the least amount of product is truly limiting. You can also verify that the limiting reactant gets completely consumed (zero moles remaining) while others have excess.

Can I use this concept with solutions and concentrations?

Absolutely. When working with solutions, first calculate moles using the molarity and volume: moles = molarity × volume (in liters). Then proceed with the standard limiting reactant calculation. This application is especially common in aqueous chemistry and laboratory reactions.