“Can You Get Shorter? Expert Insights Here”

Can You Get Shorter? Expert Insights Here

The question of whether humans can actually become shorter is more nuanced than a simple yes or no answer. While your maximum genetic height is largely determined before adulthood, several legitimate factors can cause temporary or permanent reductions in stature throughout your lifetime. Understanding these mechanisms helps explain why some people appear shorter than they once were, and what practical steps you can take to manage height changes as you age.

Height isn’t as fixed as many believe. From childhood growth spurts to age-related spinal compression, your body undergoes measurable changes in vertical dimension. Whether you’re concerned about natural height loss, looking to understand postural effects, or simply curious about the science behind human stature, this comprehensive guide explores the real ways your height can decrease and what experts recommend for maintaining optimal spinal health and posture throughout your life.

Understanding Natural Height Loss

Yes, you absolutely can get shorter—and it’s far more common than most people realize. Research from medical institutions consistently shows that adults lose measurable height as they progress through middle and older age. The average person loses approximately one-half inch of height per decade after age 40, with the rate of loss accelerating after age 70. This isn’t a myth or misconception; it’s a well-documented physiological reality supported by gerontologists and orthopedic specialists worldwide.

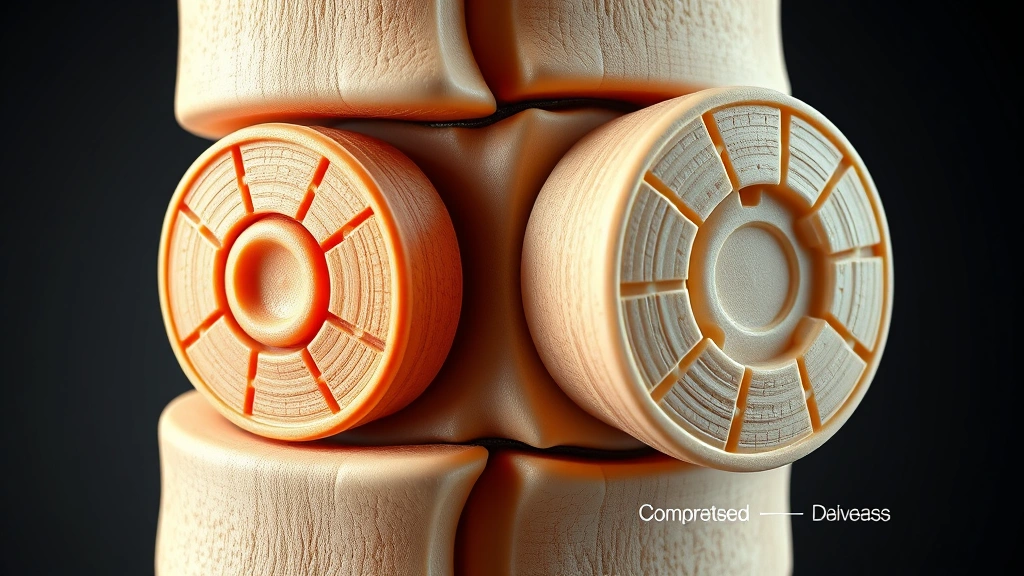

The primary culprit behind natural height loss is intervertebral disc degeneration. Your spine consists of 33 vertebrae separated by cushioning discs filled with fluid. Over time, these discs lose water content and compress, reducing the space between vertebrae. Additionally, vertebral bodies themselves can lose bone density through a process called osteoporosis, leading to micro-fractures and further compression. Unlike structural home repairs that require immediate attention, spinal compression happens gradually and subtly over years or decades.

Women typically experience more significant height loss than men, particularly after menopause when estrogen levels decline dramatically. Estrogen plays a crucial role in maintaining bone density, and its reduction accelerates bone loss in women. Studies indicate that women lose an average of 2-3 inches over their lifetime, while men lose approximately 1-2 inches, though individual variation is substantial.

Age-Related Spinal Compression

The spine’s structural integrity directly determines your height, making spinal compression the most important factor in understanding how you can get shorter. Your intervertebral discs act like shock absorbers, and as they dehydrate and flatten with age, your vertebral column literally shortens. This process accelerates when combined with gravity’s constant downward force and repetitive spinal stress from daily activities.

Vertebral compression fractures represent another significant mechanism of height loss, especially in individuals with osteoporosis. These fractures often occur without trauma—sometimes simply from sneezing, coughing, or bending forward. The vertebra collapses partially, reducing its height and subsequently reducing overall stature. A single compression fracture can cause a loss of half an inch or more, and multiple fractures compound the effect considerably.

The cervical spine (neck region), thoracic spine (mid-back), and lumbar spine (lower back) all contribute to total height, but the lumbar and thoracic regions account for most height-related changes. Kyphosis, an excessive forward curvature of the thoracic spine, commonly accompanies age-related height loss. This postural change not only reduces measured height but also affects how tall you appear and can impact breathing and digestive function.

Medical professionals measure height loss through longitudinal studies and spinal imaging. X-rays and MRI scans reveal disc space narrowing, vertebral body height reduction, and structural changes invisible to the naked eye. If you’re concerned about significant height loss, requesting these diagnostic tools from your healthcare provider can identify specific structural changes and guide treatment decisions.

Posture and Apparent Height Reduction

Beyond actual structural changes, posture dramatically affects how tall you appear and even how much you measure in clinical settings. Poor posture—characterized by rounded shoulders, forward head position, and spinal flexion—can make you appear 1-2 inches shorter than your actual spinal length. This is separate from genuine structural height loss but equally important to address for health and appearance.

Rounded shoulders and forward head posture result from prolonged sitting, repetitive strain, and muscle imbalances. Modern lifestyles featuring desk work, smartphone use, and computer screens actively promote poor posture. Over months and years, these postural habits can become habitual, with muscles adapting to shortened, rounded positions. Your pectoralis major and minor muscles tighten, while your rhomboids and upper back extensors weaken, perpetuating the slouched position.

The good news is that postural height reduction is largely reversible through targeted exercises and conscious habit changes. Standing tall with shoulders back, chest open, and spine extended can immediately restore 1-2 inches of apparent height. More importantly, maintaining proper posture long-term prevents additional structural damage and may slow age-related height loss. Think of it like maintaining a home’s structural integrity—preventive measures prove far more cost-effective than addressing damage after it occurs.

Interestingly, height measurement itself varies based on posture and time of day. You’re typically taller in the morning before gravity and daily activities compress your discs, and shorter by evening. This diurnal variation can amount to 0.5-1 inch of difference, demonstrating how disc fluid shifts throughout the day. Proper posture minimizes this variation and maintains more consistent height throughout your day.

Medical Conditions That Cause Height Loss

Several specific medical conditions accelerate height loss beyond normal aging. Osteoporosis stands as the most prevalent culprit, particularly affecting women over 50 and men over 70. This condition reduces bone mineral density, making vertebrae more susceptible to compression fractures and structural collapse. The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates that one in three women and one in five men over age 50 will experience osteoporosis-related fractures.

Ankylosing spondylitis, a type of inflammatory arthritis affecting the spine, causes vertebrae to fuse together and often results in severe kyphosis and height loss. Rheumatoid arthritis can similarly damage spinal structures, particularly the cervical spine, leading to measurable stature reduction. Degenerative disc disease, distinct from normal aging, involves accelerated disc degeneration and may require specific medical intervention.

Multiple myeloma, a blood cancer affecting bone marrow, commonly causes vertebral compression fractures and significant height loss in affected patients. Paget’s disease of bone, though rare, causes abnormal bone remodeling that can affect vertebral structure. Scoliosis and kyphosis, whether developmental or age-related, directly reduce height through spinal curvature. Even conditions like severe malnutrition or hormonal imbalances can affect bone density and spinal health.

Certain medications, particularly long-term corticosteroid use, accelerate bone loss and increase fracture risk. If you take chronic medications, discussing their effects on bone health with your physician helps identify potential height-loss risks early. Early intervention for these conditions can significantly slow or halt progressive height loss.

Practical Steps to Maintain Height

Understanding how you can get shorter empowers you to take preventive action. The most effective strategy involves maintaining robust bone density through adequate calcium and vitamin D intake. The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends 1,000-1,200 mg of calcium daily for adults, with specific requirements varying by age and sex. Vitamin D, essential for calcium absorption, requires 600-800 IU daily for most adults, though some experts advocate higher amounts for optimal bone health.

Weight-bearing exercise provides the most powerful stimulus for maintaining bone density. Activities like walking, jogging, dancing, and resistance training stress bones in ways that signal your body to maintain mineral content. Research consistently demonstrates that people maintaining regular exercise throughout adulthood experience significantly less age-related height loss. Aim for 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly, combined with resistance training 2-3 times weekly.

Protein intake directly supports bone health and muscle mass that protects your spine. Most adults require 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily, though older adults may benefit from higher amounts. Adequate protein consumption combined with resistance exercise maintains the muscular support system that stabilizes your spine and reduces injury risk.

Avoiding smoking and limiting alcohol consumption protect bone health significantly. Smoking reduces bone density by up to 10% and interferes with calcium absorption. Excessive alcohol consumption similarly impairs bone metabolism. These lifestyle modifications cost nothing but provide substantial protective benefits for your skeletal system.

Regular spinal health assessments help identify problems early. If you notice significant height loss—more than 1-2 inches over several years—consult your healthcare provider. Imaging studies can reveal structural changes requiring intervention. Bone density screening (DEXA scans) at appropriate ages identifies osteoporosis risk before fractures occur, allowing preventive treatment with proven medications if necessary.

Daily Habits for Optimal Spinal Health

Maintaining proper posture throughout daily activities represents your most practical tool for preventing apparent height loss and protecting spinal structures. When sitting at desks or using computers, position your screen at eye level, keep your shoulders relaxed, and maintain lumbar spine support. Many people benefit from ergonomic office furniture, standing desks, or supportive office chairs that promote neutral spine positioning.

Strengthen your core muscles through targeted exercises that support your spine. Planks, bird dogs, dead bugs, and bridges activate deep abdominal muscles and spinal stabilizers without excessive spinal loading. Yoga and Pilates, when performed correctly, build postural awareness and functional strength. Physical therapists can design personalized programs addressing your specific weaknesses and imbalances.

Sleep position significantly impacts spinal health. Side sleeping with a pillow between your knees and proper head support maintains neutral spine alignment. Back sleeping with pillow support under your knees also works well for many people. Avoid stomach sleeping, which twists your cervical spine and strains your lower back. Quality sleep allows your discs to rehydrate, partially reversing daily compression—another reason why morning height exceeds evening height.

Lifting mechanics prevent acute spinal injuries that accelerate degeneration. Always bend at your hips and knees rather than rounding your lower back. Keep heavy objects close to your body and avoid twisting while loaded. Even if you don’t lift heavy items professionally, proper lifting technique during household tasks, gardening, and everyday activities protects your spine from cumulative microtrauma.

Flexibility training, particularly gentle stretching of hip flexors, hamstrings, and chest muscles, reduces compensatory postural patterns. Tight hip flexors pull your pelvis into anterior tilt, increasing lumbar lordosis and compressing lower spine discs. Regular stretching counteracts these effects. Spend 10-15 minutes daily on flexibility work, holding stretches for 20-30 seconds without bouncing.

Stay hydrated throughout the day. Intervertebral discs absorb water through osmotic processes, and dehydration reduces disc fluid content. While hydration alone won’t prevent age-related disc degeneration, it supports optimal disc function. Most adults require 8-10 glasses of water daily, with individual needs varying based on activity level and climate.

Maintain a healthy weight through balanced nutrition and regular activity. Excess body weight, particularly abdominal fat, increases spinal compression forces and promotes postural slouching. Weight loss, when needed, reduces these stresses and often improves perceived height through better posture. Combine weight management with the exercise and nutritional recommendations previously mentioned for comprehensive spinal health.

Regular walking provides low-impact exercise supporting bone health without excessive spinal stress. Aim for 30 minutes of walking most days of the week. Walking outdoors in sunlight provides additional vitamin D synthesis, supporting calcium absorption. This simple, free activity delivers remarkable health benefits when performed consistently.

FAQ

At what age do people typically start getting shorter?

Height loss typically begins around age 40, with an average loss of approximately 0.5 inches per decade. The rate accelerates after age 70. However, individual variation is substantial—some people experience minimal height loss while others lose 1-2 inches by age 65. Starting preventive measures before age 40 helps minimize future losses.

Can you reverse height loss from aging?

Actual structural height loss from disc degeneration and vertebral compression cannot be reversed. However, apparent height reduction from poor posture can be completely reversed through postural correction and strengthening exercises. Preventing future height loss remains possible through the strategies outlined in this article, making early intervention crucial.

Is height loss a sign of serious health problems?

Gradual height loss of 0.5-1 inch over several years represents normal aging. However, rapid height loss exceeding 1-2 inches over 1-2 years warrants medical evaluation. Rapid loss might indicate osteoporosis, vertebral fractures, or other conditions requiring treatment. Always consult your healthcare provider if you notice unusual height changes.

Do men and women lose height at the same rate?

No, women typically lose more height than men, particularly after menopause. Women lose an average of 2-3 inches over their lifetime compared to 1-2 inches for men. This difference reflects women’s higher osteoporosis risk due to declining estrogen levels. Women should prioritize bone health measures earlier and more aggressively than men.

Can exercises really prevent height loss?

Yes, regular weight-bearing and resistance exercise significantly slows age-related height loss by maintaining bone density and supporting spinal structures. Studies comparing sedentary and active older adults consistently show less height loss in those maintaining regular exercise throughout adulthood. The effect is most pronounced when exercise begins before significant bone loss occurs.

How much can posture affect how tall you appear?

Poor posture can make you appear 1-2 inches shorter than your actual measured height. Correcting posture through conscious effort and strengthening exercises immediately restores this apparent height. Over time, habitual good posture prevents structural changes that would reduce actual height, making it a worthwhile investment in your long-term stature and health.

Should I see a doctor about height loss?

Gradual height loss is normal with aging, but significant or rapid loss warrants professional evaluation. If you lose more than 1-2 inches over 1-2 years, experience back pain, or notice increased spinal curvature, schedule an appointment with your primary care physician. They may recommend bone density screening, imaging studies, or specialist referral if necessary.