Finding Oblique Asymptotes: Expert Tips & Tricks

Finding Oblique Asymptotes: Expert Tips & Tricks

Oblique asymptotes, also known as slant asymptotes, represent one of the most elegant concepts in calculus and precalculus mathematics. These diagonal lines describe the behavior of rational functions as they extend toward infinity, providing crucial insight into how graphs behave at their extremes. Understanding how to find oblique asymptotes transforms your ability to sketch complex functions accurately and predict their long-term behavior with confidence.

Whether you’re a student tackling calculus homework or someone refreshing your mathematical skills, mastering oblique asymptotes opens doors to deeper comprehension of rational functions. This comprehensive guide walks you through proven techniques, real-world applications, and expert strategies that make finding these asymptotes intuitive rather than intimidating.

What Are Oblique Asymptotes?

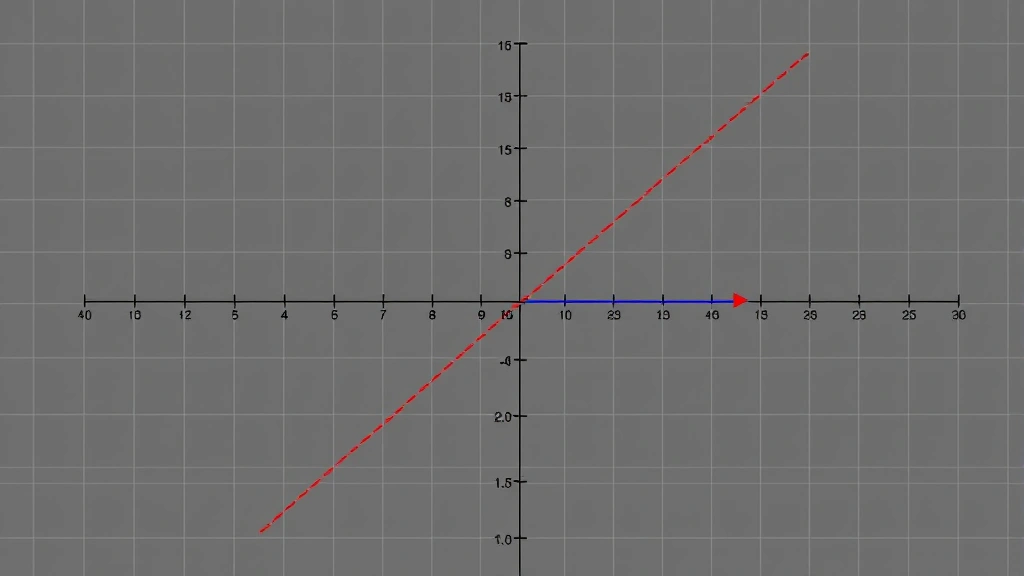

An oblique asymptote is a straight line that a curve approaches as the independent variable approaches infinity or negative infinity. Unlike horizontal asymptotes that remain flat or vertical asymptotes that shoot straight up, oblique asymptotes possess a slope—they angle diagonally across the coordinate plane. This unique characteristic makes them particularly fascinating and useful for understanding rational function behavior.

When a rational function’s numerator has a degree exactly one higher than its denominator’s degree, an oblique asymptote will exist. The equation of this asymptote line emerges directly from polynomial division, making it discoverable through straightforward algebraic manipulation. The function approaches this diagonal line but never quite reaches it, creating that characteristic asymptotic behavior we observe in graphs.

Think of an oblique asymptote as a mathematical boundary that guides the function’s trajectory. As you move further right or left on your graph, the function hugs this invisible line more and more closely. This behavior proves invaluable when sketching graphs by hand or predicting function values at extreme inputs.

Prerequisites: Essential Mathematical Foundations

Before diving into oblique asymptote calculations, you’ll need solid comfort with several foundational concepts. First, understand how to divide numbers precisely, as polynomial division mirrors this process. Second, grasp polynomial structure—recognizing degrees, terms, and coefficients becomes essential when analyzing rational functions.

You should also understand fraction multiplication and manipulation, since rational functions are essentially fractions with polynomials in numerator and denominator positions. Additionally, familiarity with finding the least common denominator helps when combining rational expressions.

Perhaps most importantly, you need comfort with basic polynomial long division. If this skill feels rusty, spend time reviewing the process: dividing the leading term, multiplying back, subtracting, bringing down the next term, and repeating. This mechanical process, performed correctly, reveals the oblique asymptote hiding within your rational function.

The Polynomial Long Division Method

Polynomial long division stands as the primary technique for finding oblique asymptotes. This method works because when you divide a rational function’s numerator by its denominator, the quotient (without the remainder) represents your oblique asymptote equation.

Here’s the step-by-step process:

- Verify degree conditions: Confirm that the numerator’s degree exceeds the denominator’s degree by exactly one. If the difference isn’t one, an oblique asymptote doesn’t exist.

- Set up the division: Write out the numerator polynomial in standard form with all terms, including zeros for missing powers. Place this inside the division bracket with the denominator outside.

- Divide leading terms: Take the leading term of the numerator and divide it by the leading term of the denominator. Write this result above the division bracket.

- Multiply and subtract: Multiply your quotient term by the entire denominator, then subtract this product from the numerator’s corresponding portion.

- Bring down the next term: Bring down the next term from the numerator and repeat the division process.

- Continue until remainder: Keep repeating until you’ve processed all numerator terms. You’ll be left with a quotient and a remainder.

- Extract the asymptote: The quotient portion (ignoring the remainder completely) represents your oblique asymptote equation.

Let’s examine a concrete example. Consider the rational function f(x) = (x² + 3x + 2)/(x + 1). The numerator has degree 2, the denominator has degree 1, so their difference is 1—perfect for an oblique asymptote.

Dividing x² + 3x + 2 by x + 1: First, x² ÷ x = x. Multiply x(x + 1) = x² + x. Subtract: (x² + 3x + 2) – (x² + x) = 2x + 2. Bring down any remaining terms (there are none in this case). Next, 2x ÷ x = 2. Multiply 2(x + 1) = 2x + 2. Subtract: (2x + 2) – (2x + 2) = 0.

Your quotient is x + 2 with remainder 0. Therefore, the oblique asymptote is y = x + 2. This line guides the function’s behavior as x approaches positive or negative infinity.

Synthetic Division Approach

While polynomial long division works universally, synthetic division offers a faster alternative when the denominator is a linear binomial of the form (x – c). This streamlined method reduces arithmetic steps and minimizes calculation errors.

Synthetic division process:

- Identify the divisor: If your denominator is (x – c), use the value c in your synthetic division setup.

- Write coefficients: List all coefficients of the numerator polynomial, including zeros for missing terms.

- Set up the tableau: Write c to the left, then place the coefficients in a row to the right.

- Bring down the first coefficient: Drop the leading coefficient straight down below the line.

- Multiply and add: Multiply this value by c, write the result under the next coefficient, then add vertically.

- Repeat the cycle: Continue multiplying the new result by c and adding down the row.

- Read your quotient: The numbers below the line represent your quotient coefficients, with the final number being your remainder.

Consider f(x) = (2x² + 5x + 3)/(x + 1). Here, c = -1 (since x + 1 = x – (-1)). Write -1 on the left, then coefficients 2, 5, 3 on the right. Bring down 2. Multiply: 2 × (-1) = -2. Add: 5 + (-2) = 3. Multiply: 3 × (-1) = -3. Add: 3 + (-3) = 0. Your quotient is 2x + 3, so the oblique asymptote is y = 2x + 3.

Synthetic division shines for speed and accuracy, particularly when working through multiple problems. However, it only applies when your denominator is linear. For higher-degree denominators, polynomial long division remains your essential tool.

Identifying When Oblique Asymptotes Exist

Not every rational function possesses an oblique asymptote. Understanding the conditions that guarantee their existence prevents wasted effort and calculation mistakes. Oblique asymptotes exist exclusively when the numerator’s degree is exactly one more than the denominator’s degree.

If the numerator’s degree equals the denominator’s degree, a horizontal asymptote exists instead, found by dividing the leading coefficients. If the denominator’s degree exceeds the numerator’s degree, the x-axis (y = 0) serves as the horizontal asymptote. Only when the specific one-degree difference exists do oblique asymptotes appear.

Consider these examples: For f(x) = (x³ + 2x)/(x² – 1), degree difference is 3 – 2 = 1, so an oblique asymptote exists. For g(x) = (x² + 1)/(x² + 2), degree difference is 2 – 2 = 0, so a horizontal asymptote exists instead (y = 1, from 1÷1). For h(x) = (x + 3)/(x² + x), degree difference is 1 – 2 = -1, so a horizontal asymptote exists (y = 0).

Always check degrees first. This quick verification saves time and ensures you’re using the appropriate asymptote-finding technique. Many students waste effort attempting polynomial division on functions that don’t qualify for oblique asymptotes—a simple degree check prevents this inefficiency.

Step-by-Step Examples and Practice

Example 1: Basic Oblique Asymptote

Find the oblique asymptote of f(x) = (x² + 4x + 5)/(x – 2).

Check degrees: numerator degree = 2, denominator degree = 1, difference = 1 ✓. Perform polynomial long division of x² + 4x + 5 by x – 2. Divide x² by x to get x. Multiply x(x – 2) = x² – 2x. Subtract: (x² + 4x + 5) – (x² – 2x) = 6x + 5. Divide 6x by x to get 6. Multiply 6(x – 2) = 6x – 12. Subtract: (6x + 5) – (6x – 12) = 17. Your quotient is x + 6 with remainder 17, so the oblique asymptote is y = x + 6.

Example 2: Oblique Asymptote with Larger Polynomials

Find the oblique asymptote of f(x) = (2x³ + 3x² – 5x + 1)/(x² + x – 2).

Check degrees: numerator degree = 3, denominator degree = 2, difference = 1 ✓. Divide 2x³ by x² to get 2x. Multiply 2x(x² + x – 2) = 2x³ + 2x² – 4x. Subtract: (2x³ + 3x² – 5x + 1) – (2x³ + 2x² – 4x) = x² – x + 1. Divide x² by x² to get 1. Multiply 1(x² + x – 2) = x² + x – 2. Subtract: (x² – x + 1) – (x² + x – 2) = -2x + 3. Your quotient is 2x + 1 with remainder -2x + 3, so the oblique asymptote is y = 2x + 1.

Example 3: Using Synthetic Division

Find the oblique asymptote of f(x) = (x² – 3x + 7)/(x – 4).

Check degrees: difference = 1 ✓. Use synthetic division with c = 4. Coefficients: 1, -3, 7. Bring down 1. Multiply: 1(4) = 4. Add: -3 + 4 = 1. Multiply: 1(4) = 4. Add: 7 + 4 = 11. Quotient is x + 1 with remainder 11, so the oblique asymptote is y = x + 1.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Mistake 1: Forgetting to Check Degree Conditions

Many students jump directly into division without verifying that an oblique asymptote actually exists. Always confirm the degree difference equals exactly one before proceeding. This simple check prevents frustration and wasted calculation time.

Mistake 2: Including the Remainder in Your Asymptote Equation

After polynomial division, you obtain both a quotient and a remainder. Only the quotient represents your asymptote—discard the remainder completely. The remainder becomes negligible as x approaches infinity, which is precisely why the quotient line serves as an asymptote. Including the remainder creates an incorrect equation.

Mistake 3: Arithmetic Errors During Division

Polynomial division involves multiple multiplication and subtraction steps where small errors compound. Double-check each multiplication and subtraction. Consider verifying your answer by multiplying quotient and divisor, then adding the remainder—this should equal your original numerator.

Mistake 4: Misidentifying Which Polynomial is Numerator vs. Denominator

In rational functions written as fractions, ensure you’re dividing the correct polynomial by the correct polynomial. The polynomial on top (numerator) goes inside the division bracket; the polynomial on bottom (denominator) goes outside. Reversing these produces an entirely incorrect result.

Mistake 5: Failing to Write Polynomials in Standard Form

Before beginning division, arrange all terms in descending order by degree. Include placeholder terms (with coefficient 0) for any missing powers. This organization prevents skipped steps and calculation errors.

Mistake 6: Confusing Oblique Asymptotes with Other Asymptote Types

Remember that horizontal asymptotes appear when degree difference equals zero, and vertical asymptotes occur at denominator zeros. Only when degree difference equals one do oblique asymptotes exist. Mixing these concepts leads to fundamental errors in function analysis.

For deeper mathematical understanding, explore how these concepts connect to finding limiting values in other mathematical contexts. The principle of identifying which factor limits behavior extends across multiple mathematical domains.

Also consider reviewing our complete guide collection for related mathematical topics that strengthen your overall quantitative skills. Building strong fundamentals in polynomial operations and rational functions creates a foundation for advanced calculus concepts.

FAQ

What’s the difference between oblique and horizontal asymptotes?

Horizontal asymptotes are perfectly flat lines that functions approach as x approaches infinity. They occur when the numerator and denominator degrees are equal (horizontal line at y = ratio of leading coefficients) or when the denominator degree exceeds the numerator degree (horizontal line at y = 0). Oblique asymptotes are diagonal lines that occur specifically when the numerator degree exceeds the denominator degree by exactly one. Functions approach these slanted lines rather than flat lines as x approaches infinity.

Can a rational function have both an oblique asymptote and a vertical asymptote?

Absolutely. A rational function can simultaneously possess one or more oblique asymptotes and one or more vertical asymptotes. Vertical asymptotes occur at values where the denominator equals zero (and the numerator doesn’t also equal zero). These represent completely different phenomena—vertical asymptotes describe discontinuities, while oblique asymptotes describe end behavior. A single function can exhibit both characteristics.

How do I know if my polynomial division is correct?

Verify your division by multiplying the quotient by the divisor and adding the remainder. This product should equal your original numerator. For example, if dividing numerator N by denominator D yields quotient Q and remainder R, then D × Q + R should equal N. If this check fails, redo your division carefully, paying special attention to arithmetic.

Why do we ignore the remainder when finding the oblique asymptote?

As x approaches infinity, the remainder (which is a lower-degree polynomial) becomes insignificant compared to the quotient (which is a linear function). The ratio of a bounded remainder to an increasingly large denominator approaches zero, so the remainder’s contribution to the function’s value vanishes. Only the quotient persists as a meaningful guide to the function’s behavior at extreme values, making it the asymptote.

Can I use synthetic division for all oblique asymptote problems?

No. Synthetic division only works when your denominator is a linear binomial of the form (x – c) or (x + c). For denominators with degree 2 or higher, you must use polynomial long division. Synthetic division is a speed optimization for the specific case of linear divisors, not a universal replacement for polynomial division.

What if the numerator and denominator share common factors?

If the numerator and denominator have common factors, simplify the rational function by canceling these factors first. This simplification may change the degree difference, potentially eliminating the oblique asymptote entirely or creating a removable discontinuity (hole) in the graph rather than a vertical asymptote. Always factor and simplify before analyzing asymptotes.