Find LCD Quickly: A Math Teacher’s Guide

Find LCD Quickly: A Math Teacher’s Guide

The Least Common Denominator (LCD) is one of those mathematical concepts that students encounter repeatedly throughout their education, from basic fraction operations in elementary school to complex algebraic equations in high school. Yet many people struggle with finding it efficiently, leading to frustration and errors in their calculations. Whether you’re helping your child with homework, brushing up on your own math skills, or teaching a classroom full of students, understanding how to find the LCD quickly can transform your approach to working with fractions.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll walk through proven methods that make finding the LCD straightforward and intuitive. You’ll learn multiple techniques suited to different situations, from simple fractions to more complex scenarios. By the end, you’ll have the tools to tackle any LCD problem with confidence and speed.

What is the Least Common Denominator?

The Least Common Denominator is the smallest positive integer that serves as a common denominator for two or more fractions. Think of it as the smallest number that all your denominators can divide into evenly. For example, if you’re working with the fractions 1/4 and 1/6, the LCD would be 12, since 12 is the smallest number that both 4 and 6 divide into without remainder.

Understanding this concept requires familiarity with a few related terms. The denominator is the bottom number in a fraction. A common denominator is any number that all denominators in a problem can divide into evenly. The LCD is simply the smallest such number. This distinction matters because while any common multiple will work for fraction operations, the LCD keeps your numbers manageable and your calculations simpler.

When you’re adding or subtracting fractions, you need a common denominator to combine them. For instance, you can’t directly add 1/3 + 1/4 without first converting them to fractions with the same denominator. The LCD tells you what that denominator should be. In this case, the LCD of 3 and 4 is 12, so you’d convert 1/3 to 4/12 and 1/4 to 3/12, allowing you to add them as 7/12.

For more foundational math concepts, check out our comprehensive how-to guides and tutorials that break down complex topics into manageable steps.

Why LCD Matters in Mathematics

The Least Common Denominator isn’t just an abstract mathematical concept—it’s a practical tool that appears throughout mathematics and real-world applications. Understanding its importance motivates learners to master the skill.

Fraction Operations: The primary use of LCD is enabling addition and subtraction of fractions. Without finding the LCD first, these operations become impossible. When you’re adding 2/5 + 3/8, you must first convert both fractions to equivalent fractions with a common denominator—in this case, 40.

Algebra and Beyond: As mathematics becomes more advanced, the LCD concept extends to algebraic fractions. When solving equations or simplifying rational expressions, you’ll frequently need to find the LCD of polynomial denominators. The same principles apply, just with more complex expressions.

Real-World Applications: Recipes, construction measurements, financial calculations, and scientific formulas all involve fractions. Being able to quickly combine fractional amounts saves time and reduces errors. A carpenter might need to add measurements like 2 3/8 inches + 1 5/16 inches, which requires finding the LCD.

Building Mathematical Foundation: Mastering LCD strengthens your understanding of factors, multiples, and number relationships. These foundational skills support learning in algebra, geometry, and higher mathematics.

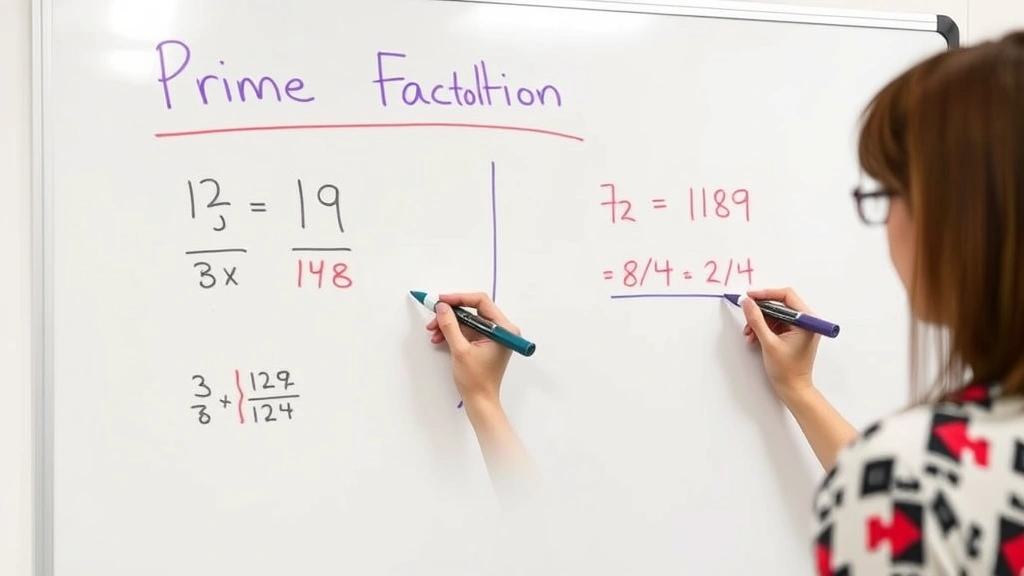

Method 1: Finding LCD Using Prime Factorization

Prime factorization is often considered the most reliable method for finding the LCD, especially when working with larger numbers or multiple fractions. This method works by breaking each denominator into its prime factors, then using those factors to build the LCD.

Step 1: Find Prime Factors of Each Denominator

Start by listing the prime factors of each denominator. Prime numbers are numbers greater than 1 that have no positive divisors other than 1 and themselves (2, 3, 5, 7, 11, etc.). For example:

- 12 = 2 × 2 × 3 (or 2² × 3)

- 18 = 2 × 3 × 3 (or 2 × 3²)

- 8 = 2 × 2 × 2 (or 2³)

Step 2: Identify All Unique Prime Factors

List each prime factor that appears in any of your denominators. From the example above, the unique prime factors are 2 and 3.

Step 3: Use the Highest Power of Each Prime Factor

For each unique prime factor, use the highest power that appears in any denominator. In our example:

- The highest power of 2 is 2³ (from 8)

- The highest power of 3 is 3² (from 18)

Step 4: Multiply to Find the LCD

Multiply these highest powers together: 2³ × 3² = 8 × 9 = 72. Therefore, the LCD of 12, 18, and 8 is 72.

This method is particularly effective because it’s systematic and works for any set of numbers. Once you master prime factorization, you have a tool that never fails.

Method 2: Listing Multiples

For smaller numbers or when you need a quicker approach, listing multiples is often the fastest method. This technique involves writing out the multiples of each denominator until you find one that appears in all lists.

Step 1: List Multiples of Each Denominator

Write out several multiples of each denominator. For example, to find the LCD of 4 and 6:

- Multiples of 4: 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36…

- Multiples of 6: 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42…

Step 2: Find the First Common Multiple

Look for the smallest number that appears in all your lists. In this case, 12 appears in both lists first, so 12 is the LCD of 4 and 6.

When to Use This Method:

The listing multiples method works best when:

- You’re working with small numbers (under 20)

- You need a quick answer and don’t need to show extensive work

- You’re helping younger students understand the concept intuitively

- You only have two denominators to work with

This method is less efficient with larger numbers or when dealing with three or more denominators, as your lists become very long.

Method 3: Using the GCF Approach

The third major method involves the Greatest Common Factor (GCF), also called the Greatest Common Divisor (GCD). This approach uses the mathematical relationship between GCF and LCD to find your answer efficiently.

The Formula:

For two numbers, the relationship is: LCD(a,b) × GCF(a,b) = a × b

Rearranging: LCD(a,b) = (a × b) ÷ GCF(a,b)

Step 1: Find the GCF of the Denominators

The GCF is the largest number that divides evenly into all your denominators. For 12 and 18, the factors are:

- Factors of 12: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12

- Factors of 18: 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 18

- Common factors: 1, 2, 3, 6

- GCF = 6

Step 2: Apply the Formula

LCD(12, 18) = (12 × 18) ÷ 6 = 216 ÷ 6 = 36

This method is particularly elegant because it demonstrates the mathematical relationship between these concepts. For more practical problem-solving approaches, explore our guide on how to endorse a check, which teaches similar step-by-step methodologies.

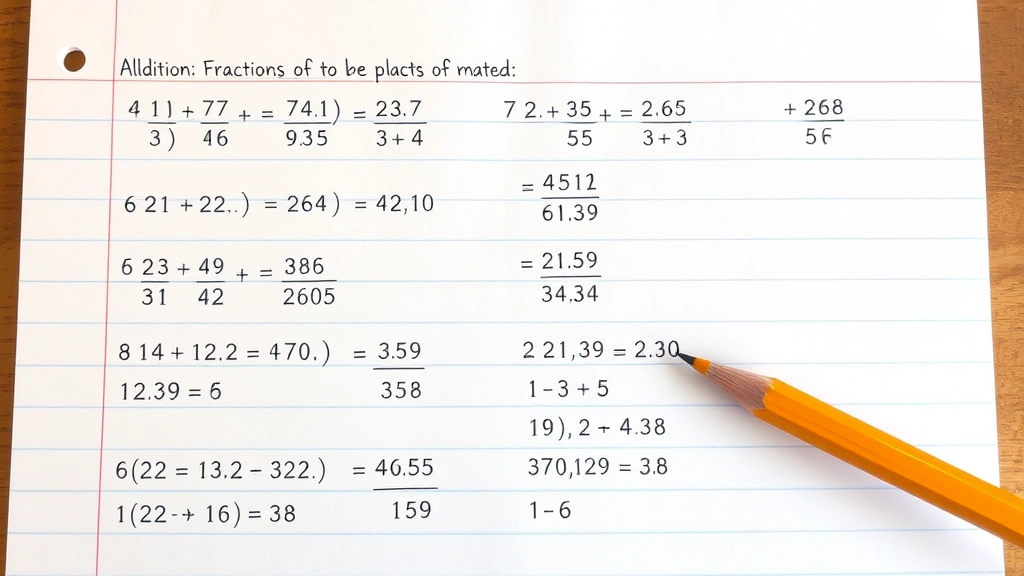

Practical Examples and Step-by-Step Solutions

Let’s work through several real-world examples using different methods to solidify your understanding.

Example 1: Adding Simple Fractions

Problem: Calculate 1/6 + 1/8

Solution using Prime Factorization:

- 6 = 2 × 3

- 8 = 2³

- LCD = 2³ × 3 = 24

- Convert: 1/6 = 4/24 and 1/8 = 3/24

- Answer: 4/24 + 3/24 = 7/24

Example 2: Working with Three Fractions

Problem: Calculate 1/4 + 1/6 + 1/8

Solution using Prime Factorization:

- 4 = 2²

- 6 = 2 × 3

- 8 = 2³

- LCD = 2³ × 3 = 24

- Convert: 1/4 = 6/24, 1/6 = 4/24, 1/8 = 3/24

- Answer: 6/24 + 4/24 + 3/24 = 13/24

Example 3: Larger Numbers

Problem: Find LCD of 20, 30, and 45

Solution using Prime Factorization:

- 20 = 2² × 5

- 30 = 2 × 3 × 5

- 45 = 3² × 5

- LCD = 2² × 3² × 5 = 4 × 9 × 5 = 180

Example 4: Real-World Application

Problem: A recipe calls for 3/4 cup of flour and 1/3 cup of sugar. How much total dry ingredients do you need?

Solution:

- LCD of 4 and 3 is 12

- 3/4 = 9/12 and 1/3 = 4/12

- Total: 9/12 + 4/12 = 13/12 = 1 1/12 cups

These examples demonstrate how the methods work in practice and show why finding the LCD correctly is essential for accurate calculations.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even experienced mathematicians can make errors when finding the LCD. Being aware of common pitfalls helps you avoid them.

Mistake 1: Confusing LCD with LCM

While related, the LCD specifically refers to denominators, while LCM (Least Common Multiple) is a broader term. However, when finding the LCD of fractions, you’re actually finding the LCM of the denominators, so the concepts are intertwined.

Mistake 2: Using Any Common Denominator

Some students use any common denominator rather than the least common denominator. While this technically works, it results in larger numbers and more complicated calculations. Always aim for the smallest common denominator.

Mistake 3: Forgetting to Convert All Fractions

When adding or subtracting fractions, convert all fractions to the LCD, not just some of them. This is a frequent error that leads to incorrect answers.

Mistake 4: Arithmetic Errors in Prime Factorization

When breaking numbers into prime factors, ensure you’ve correctly identified all factors. Double-check by multiplying your factors back together to verify you get the original number.

Mistake 5: Not Simplifying the Final Answer

After performing operations with fractions, always check if your answer can be simplified. For example, 6/12 should be simplified to 1/2.

Tips for Teaching LCD to Students

If you’re an educator or parent helping students understand LCD, these strategies make the concept more accessible and engaging.

Start with Concrete Examples

Begin with physical objects or visual representations. Use pie charts, fraction bars, or actual objects divided into parts. Seeing fractions physically helps students understand why a common denominator is necessary.

Progress from Simple to Complex

Start with fractions having small, simple denominators (like 2, 3, 4) before moving to larger numbers. Success with simple problems builds confidence for tackling difficult ones.

Use Multiple Methods

Teach several methods so students can choose the approach that makes most sense to them. Some students are visual and prefer listing multiples, while others are more systematic and prefer prime factorization.

Connect to Real-World Scenarios

Use cooking, construction, sports statistics, or other real-world contexts where fractions appear. This demonstrates why LCD matters beyond abstract mathematics.

Provide Plenty of Practice

Mastery requires repetition. Provide varied problems that challenge students while building confidence. Mix different denominator sizes and numbers of fractions.

Encourage Mental Math

For simple problems, encourage students to find the LCD mentally before resorting to written methods. This strengthens their number sense and builds fluency.

For additional learning approaches, check out our step-by-step how-to guides that break down complex processes into manageable components.

FAQ

What’s the difference between LCD and GCF?

The LCD (Least Common Denominator) is the smallest number that all denominators divide into evenly. The GCF (Greatest Common Factor) is the largest number that divides evenly into all numbers. They’re inverse concepts—LCD involves multiples, while GCF involves factors. For finding LCD of fractions, you’re working with multiples of denominators.

Can the LCD ever be the same as one of the denominators?

Yes, absolutely. If one denominator is a multiple of the others, that denominator is the LCD. For example, the LCD of 3 and 6 is 6 because 6 is already a multiple of 3. Similarly, the LCD of 4, 8, and 16 is 16.

How do I find the LCD of three or more fractions?

The process is the same regardless of how many fractions you have. Using prime factorization, find the prime factors of all denominators, then use the highest power of each prime factor. Using the listing method, list multiples of each denominator until you find one that appears in all lists.

Is there a quick way to find LCD mentally?

For small denominators, yes. With practice, you can recognize patterns. For instance, if one denominator is a multiple of another, the larger is the LCD. If denominators share no common factors (coprime), multiply them together to get the LCD. However, for complex situations, written methods are more reliable.

Why do we need LCD for adding fractions but not multiplication?

When multiplying fractions, you simply multiply numerators together and denominators together. The operation doesn’t require common denominators. However, adding and subtracting require combining parts of a whole, which demands a common denominator to ensure the parts represent the same size.

What if the denominators are already the same?

If all fractions already have the same denominator, that denominator is the LCD. You can proceed directly to adding or subtracting the numerators without any conversion.

How does finding LCD relate to fraction simplification?

LCD and simplification are related but opposite processes. When finding LCD, you’re expanding fractions to larger, equivalent forms with a common denominator. When simplifying, you’re reducing fractions to smaller, equivalent forms. Both rely on understanding equivalent fractions.